В Японии умерла женщина, первая покорившая Эверест

В Японии умерла женщина, которая первая покорила Эверест среди женщин.

Первая женщина, впервые покорившая Эверест и Семь вершин мира скончалась утром 20 октября.Причиной смерти Дзюнко Табэи стала болезнь, побороть которую японка не смогла.Перитониальный рак забрал жизнь 78-летней альпинистки.Жительница Фукусима в 35 лет стала первой среди женщин, покорившей Эверест.В 1992 году Дзюнко Табэи смогла покорить семь вершин всех континентов и стать первой женщиной и в этой программе.

(Source : http://newstes.ru/2016/10/22/v-yaponii-umerla-zhenschina-pervaya-pokorivshaya-everest.html)

In this year July, she climbed Mt.Fuji with high school students (They are victim by big earthquake and tsunami in March 2011) . It is last climbing for her climbing life that more than 50 years.

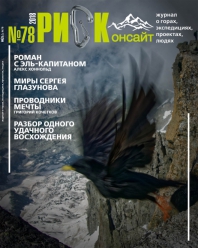

ПЕРВАЯ ЛЕДИ

Обычно летом, во время массового паломничества на Эльбрус, небольшой спасательный отряд постоянно дежурил на «Приюте одиннадцати». Спасатели старались дать консультации по тактике восхождения. Иногда охлаждали горячие головы, готовые, например, штурмовать Гору в обычной обуви или явно не подготовленные для этого предприятия. В разгар сезона спасатели выше скал Пастухова всегда устанавливали на снегу вешки, по которым в непогоду можно было бы альпинистам ориентироваться на склоне. К сожалению, довольно часто приходилось мчаться наверх за попавшими в беду восходителями. Во время отборок в гималайские экспедиции некоторые спортсмены проходили участок от «Приюта 11» до седловины за час с небольшим. За плечами у них никакого груза не было, а спасатель всегда нес с собой аптечку, продукты, запасную одежду, иногда кислородный баллон, преодолевая расстояние от «Приюта» до седловины за два часа пятнадцать минут. И это при сильном ветре, а порой в пургу. Каковы усилия при таком движении на высоте пяти и более тысяч метров, может оценить лишь человек, прошедший сам этот участок в подобном темпе. Кроме того, спасателям необходимо распределить свои усилия так, чтобы хватило сил на оказание первой медицинской помощи и транспортировку постра-давшего вниз. Запредельные нагрузки при дефиците кислорода – вот что испытываешь при таком движении.

В одно из таких дежурств Леонид Андреев, менеджер международного альпинистского лагеря, сообщил мне по рации, что наверх поднимается группа из тринадцати японцев во главе с Джункой Табей. Мы, обычно, спокойно относились к особам с известными именами, появлявшимся в зоне нашего внимания. В конечном счете, как это не банально звучит, все они – потенциальные клиенты спасателей. Гора всех уравнивает. Но в данном случае я проявил интерес. Ведь Табей – первая женщина планеты, взошедшая на самую высокую гору Земли – на Эверест (8848 метров над уровнем моря). Леонид, с которым мы много лет проработали в Контрольно-спасательном пункте, вместе ходили на горы, попросил уделить ей внимание. По плану Джунка и ее партнеры в первый день пребывания в Приэльбрусье должны были остановиться в гостинице «Иткол». Но они посчитали, что предшествующего восхождения на высшую точку Африки – шеститысячный Килиманджаро, – достаточно для акклиматизации, и сразу направилась на «Приют 11». Не учли японцы нашей тогдашней советской действительности. Обычно иностранцы, выходя в высокогорную зону, обеспечивались продуктами, которые заранее выписывались в бухгалтерии гостиницы. Но прибыли они в пятницу, в конце рабочего дня, когда сотрудники обслуживающей сферы уже ушли домой. А впереди – выходные и выдавать продукты никто не будет. Все это по рации Леня мне объяснил и попросил как-нибудь сутки японцев поддержать продуктами. Конечно, это не функции спасателей, но что не сделаешь, если просит кореш.

Когда отправляешься на высокогорное дежурство, тащишь на себе строго рассчитанные на период пребывания там вещи и продукты. Поэтому у нас было не густо с продуктами. А тут еще тринадцать дополнительных ртов. Зашел к коменданту «Приюта» Косте Хапаеву и попросил в долг буханку хлеба и пачку сахара, чем он по-приятельски поделился со мной. А у нас в достатке были чай и печенье. Предположил, что вечер и утро продержимся, а днем Андреев обещал разбиться в лепешку, но продукты раздобыть и доставить клиентам наверх. Радушно встретил японцев, общаясь с ними через переводчика, сопровождавшего их. Шура, так звали переводчика, учился на последнем курсе московского института иностранных языков и довольно бойко общался со своими подопечными. Худой, длинный паренек ничего общего с альпинизмом никогда не имел. От высоты 4200 ему поплохело, но держался парень мужественно и старался переводить как можно лучше. Из талой снеговой воды я сварил чай и, пригласив гостей в кают-компанию на втором этаже «Приюта», выложил на стол добытую буханку хлеба и наш сахар с печеньем. Поедая скромные порции, японцы оживленно расспрашивали о специфике восхождения на нашу Гору. Затем, вдруг, как по команде все встали и пошли отдыхать, сказав, что ночью выйдут на восхождение. Пытался объяснить, что в первые сутки нужно пройти акклиматизацию, поднявшись сначала к скалам Пастухова и только на следующие сутки, при хорошем самочувствии и погоде, можно выходить на гору. Предупредил, что появившиеся на небосклоне перистые облака (cirus) и застрявшее между вершинами Эльбруса чечевицеобразное облако – явные признаки наступающей в ближайшие часы непогоды. Они, улыбавшись, поблагодарили за рекомендации, но решение не изменили. Ну что ж, вольному воля.

Утром проснулся от воя ветра. Пуржило. Японцы уже ушли. Через час с небольшим, пройдя вверх всего метров триста, они вернулись. По выражению лиц восходителей было видно, что эта кратковременная вылазка им досталась не просто. Опять угощаю чаем с тем же хлебом и сахаром. А тут Леня по связи сообщает, что ничего из продуктов, к сожалению, не может раздобыть.

В обед японцы достают маленькие пакетики из своего неприкосновенного запаса, распускают содержимое в горячей воде и, ловко орудуя палочками, поглощают бурду, похожую на рисовую кашицу. Подарив свои палочки, они тщетно пытались учить меня ими пользоваться. Так проходит субботний день.

Несмотря на шквальный ветер, в ночь на воскресенье они снова выходят наверх. Видимости почти нет. Подождав пару часов, осознавая опасность, которая им грозит в такую погоду, выхожу наверх. Чуть выше скал Пастухова догоняю группу из девяти человек. Японцы еле двигаются. Пройдя с ними вверх еще с час, предлагаю на плохом английском спуститься в «Приют». Посовещавшись между собой, они уныло побрели вниз. А я, продолжая подъем, прохожу косую полку и, выйдя на седловину, встречаю Джунку Табей и трех ее подруг – очень миниатюрных девушек. Они уже сходили на Восточную вершину и потихоньку спускаются.

Многие говорят, что альпинизм из-за огромных физических нагрузок не женский вид спорта. Но мне кажется, что во время восхождения на вершину важнее воля и стремление к выживаемости, а этого у женщин, посвятивших себя нашему спорту, не занимать.

Чувствуется, как много сил отдали девушки Эльбрусу. Они едва держать-ся на ногах. Достаю термос с горячим чаем, угощаю. Немного ожили. Забираю у них рюкзаки и иду рядом. Японки постоянно валятся от усталости на снег, но идут. А ведь даже Норгей Тенсинг – первый в мире человек, взошедший на Эверест, пытался взойти на наш Эльбрус и не смог, отшутившись тем, что гора не хочет его принять.

По рации прошу выйти навстречу к нам спасателей, дежуривших на «Приюте». Японцы планировали спуститься на лыжах с Эльбруса, но сил хватило лишь на то, чтобы дотащить ски-туры только до скал Пастухова. Теперь нужно было забрать снаряжение и довести обессиливших восходителей до Приюта. Сопровождая японок, помогаю подняться со снега то одной барышне, то другой. Лучше других чувствует себя Табей, но тоже еле передвигается. Подбадриваю их, угощая теплым чаем. Перед «Приютом» ускоряюсь, чтобы до прихода девушек вскипятить чай.

В кают-компании Джунка с друзьями увидела на столе все то же меню. А в это время ввалилась в гостиницу группа американцев, в сопровождении известного альпиниста Валентина Иванова. Шум и смех наполнили небольшое помещение столовой. Помощники Иванова быстро сервировали столы, выставив свежие овощи и фрукты, колбасы, паюсную икру и прочую калорийную вкуснятину. Валентин, представив меня американцам, рассказал о работе нашей спасслужбы и пригласил к столу. Стало неловко. Слишком разительно отличалось американское меню от японского. Посидев для приличия, несколько минут с новыми гостями, я вернулся к нашему с японцами убогому столу. Обращаясь ко мне на ломаном английском вперемежку с японскими словами, Джунка пыталась мне что-то сказать, с каждой фразой все больше раздражаясь. Прошу переводчика перевести ее претензии.

– Вы относитесь к белым лучше, чем к нам, желтым. Почему у американ-цев на столе такое обилие продуктов, а у нас нет? Где наши гиды? Где высотные носильщики? Почему вы не обеспечили нам восхождение? Ведь мы за все вам заплатили.

– Объясни ей, что она меня принимает не за того. Я спасатель, и моя здесь обязанность оказывать помощь всем восходителям – белые они или серо-буро-малиновые в полосочку. Кроме того, мы еще предупреждаем их о возможных опасностях на горе. И не наши проблемы, если восходители игнорируют советы и их восхождение срывается. О продуктах, гидах и носильщиках – это вообще не ко мне.

– Вы же помогали нам на спуске, но это недостаточно. Вы здесь представитель своей страны и обязаны обеспечить восхождение на вершину всей группе.

– За всю советскую власть и, тем более, за людей, пригласивших Вас, уважаемая Джунка, на Эльбрус и получивших за это деньги, я ответствен-ности не несу. А то, что я помогал, то делал это не по обязанности, а потому что уважаю Вас как первую леди в альпинизме, сумевшую взойти на Эверест.

Джунка, несколько успокоившись, пригласила меня к себе в каюту и показала контракт. Переводчик дословно перевел написанное в этой бумаге. И тут в недоумении оказался я. В договоре с Совинтерспортом было оговорено, что группе под руководством Табей для восхождения на Эльбрус предусмотрено выделение каждому из тринадцати японских альпинистов по гиду, а четырнадцатый гид во время восхождения должен идти впереди группы, предупреждая о возможных ледовых трещинах, встречающихся по пути подъема. Кроме того, вещи японцев должны нести пять высотных носильщиков. Естественно оговаривалось, что питание клиентов будет высококалорийным, и принимающая сторона гарантировала, что все тринадцать человек выйдут на вершину. За эти услуги каждый японец проплатил в Москве по тысяче долларов за день пребывания в Приэльбрусье. Всего за услуги уплачено семьдесят восемь тысяч долларов. Пытаюсь Джунке объяснить, что я к контракту не имею никакого отношения, однако, как мне показалось, она этому не поверила. Кстати, Лене Андрееву дельцы из интерспорта тоже ничего не сообщили об условиях контракта. Когда утихла непогода, японцы попрощались и ушли вниз.

Через три месяца я получил из Японии от Джунки Табей очень теплое письмо с извинениями и наилучшими пожеланиями. В письме она передала мне фотографии и написала, что разобралась, кто есть кто.

А через некоторое время я ощутил, что такое альпинистская солидар-ность.

После чернобыльской катастрофы увеличилась щитовидная железа у моей дочки. Врачи порекомендовали употреблять в пищу консервированную ламинарию. Связался я с бакинскими друзьями, попросив у них капусту. Подумав вначале, что мне нужны доллары, они готовы были оказать материальную помощь. Но когда оказалось, что нужны натуральные консервы из морской капусты, мой друг Расим Джафаров, инструктор альпинизма, партнер по связке, тут же выслал их в большом количестве. Кроме того, я узнал, что в Японии разработана методика лечения с использованием лекарства, дающего положительные результаты. В отчаянии, без всякой надежды на положительный результат, послал письмо Джунке Табей, и она сразу же выслала необходимые лекарства. В результате, благодаря усилиям друзей, моя дочь выздоровела.

Английский вариант:

JUNKA TABEI, THE LADY-CLIMBER

Usually a small rescue team was always on duty at the Shelter of the Elevens during mass pilgrimages to Elbrus. The rescuers would try to advise the climbers on the ascent of the Mountains as to both tactics and technique. At times they had to damp the bold spirits’ ardour. Some of them, prompted by their irrepressible vigour, were ready to rush Elbrus in civvies and not duly trained for the task. At the height of the season the rescuers used to drive wands into the ice above the Pastukhov Rocks so that the climbers could find their bearings on the slope in case of a bad weather. Unfortunately, the rescuers often had to tear uphill at a mad pace in search of the mountaineers who had got into trouble. During qualification rounds some of the contenders for Himalaya expeditions membership used to traverse the section of the route to the summit starting from the Shelter up to the Col within an hour odd. But they hadn’t got on his back any burden weighing down – in contrast to a rescuer who always ought to have by him a first-aid kit, provision, spare clothes, and sometimes an oxygen cylinder. With such a load he would get to the Col, starting from the Shelter, within two hours odd. This is exhausting as it is. Add here a strong wind and a snow storm at times, and it can give you an idea of what strain one have to bear at such a pace at an altitude of 5000 m and more above sea level. But to see it in proper perspective, fully conversant with the matter, one must walk in person this section of the route at such a pace. Moreover, the rescuers have to spare their strength while walking so that they could render first-aid and secure evacuation. The overwork as a result of oxygen starvation is beyond the limits.

The case I am about to tell happened during my duty. Leonid Andreev, a manager of the international mountaineering camp, told me over the wireless that there was going up to us a group of thirteen Japanese climbers headed by a certain Junka Tabei. As a rule, we were at ease in the presence of persons of high standing. As a matter of fact, both ordinary people and eminent ones are the rescuers’ potential clients. The Mountain makes level all of us. Yet for this once the person in question intrigued me very much. The point is that Tabei was the first woman to climb up to the top of Everest, the highest mountain of the world (8848 m above sea level). Leonid, my pal with whom I had been many years working at the Rescue post and climbing different routes and mountains, asked me to give particular attention to her. According to their plan, on the first day of their arrival in Baksan valley they should put up at the hotel ‘Terscol’. But they considered themselves acclimatized prior to it when climbing Kilimanjaro (6000 m above sea level) not long ago and at once made for the Shelter of the Elevens. Last but not least – only one thing but the decisive one the Japanese failed to take into consideration: our Soviet reality of those distant days. Usually the foreigners who were going to the alpine region, were supplied with provision which in good time was to be ordered at the counting house of the hotel. The Japanese however arrived on Friday at the end of the working day when the employees had already gone home. The weekend was in prospect, and nobody was eager to issue the supplies till Monday. All this was told over the wireless. Leonid cleared up the situation and asked a favour of me – somehow to support the Japanese with victuals, to put them down for allowance if only for a day. Why, what wouldn’t you do for your pal’s sake even if it weren’t the rescuers’ official duties.

When you are going to the Alpine zone to take over the watch you take with you things, gear, comestibles, and other stuff like that meant for a set time-limit. That’s why we were a bit pushed for food and, in addition, we had some thirteen mouths more to feed in our Alpine family. I called Kostya Khapaev, the warden of the Alpine hostel and begged of him on trust for a loaf of bread and a pack of sugar. He shared these frugal victuals with me in a friendly manner. Tea and biscuits we had plenty of them. All the same nothing else we had got. Suppose we hold out this evening and far tomorrow morning. What next? Andreev promised to lay himself out but procure some provision tomorrow afternoon and to supply those above with them.

I possibly gave the Japanese a hearty welcome while talking with the guests through an interpreter. The latter had been attending them as far as the Shelter. Shura (diminutive of Alexandr. – translator’s note) – the way the lad was called – was a student in his final year of the Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages, and he was glibly speaking to his wards. Slim, tall, he had nothing to do with mountaineering. He felt unwell due to an altitude of 4200 m above sea level but the lad was trying to bear up as beseems the man, doing his best as to the interpretation.

I made tea of water from melted snow and invited our guests upstairs in the ward-room, having laid out on the table the procured loaf of bread and sugar with biscuits of our own. Eating up their frugal supper, the Japanese were questioning us with animation about the ascent of our mountain and its peculiarities. Then, all of a sudden, all of them stood up as one man and went to bed, saying to us that they were going to climb at night. I tried to convince them of the necessity of acclimatization. At first it might be as well to ascend up to Pastukhov Rocks and only then, provided one feels quite oneself and it is fine, it were advisable to go to the summit. I forewarned them of cirri that had appeared in the sky and of a lens-like cloud that had got stuck between the two summits of Elbrus, which clearly foreboded a foul weather to come within the next few hours. Smiling at me they thanked me for an advice but didn’t change their mind. Well, every man is his own master. As you like, as you please.

Early in the morning I woke up from the wailing of wind. There was a snow-storm outside. The Japanese had already gone off. In an hour odd they returned after they had climbed the slope some three hundred metres. To judge by their appearance, the cragsmen and cragswomen didn’t like their first excursion. Well, once again I treated them to the same bread and sugar. Here Leonid let us know by radio that the pity of it but he had not managed to get any provision.

The lunch-hour came, and the Japanese took small bags of their iron ration and dissolved their content in hot water. Then, knowing how to use chopsticks, they absorbed it, a kind of rice soup. Presenting me with the same chopsticks, they made an attempt to teach me using this quaint tool but their labor was lost. The whole Saturday passed like that.

In spite of the squally wind they again went climbing on the night of Sunday. The field of vision was reduced almost to nought. After I had been waiting for them for about two hours I began to feel uneasy. Such weather is pregnant. Having prepared for a journey uphill, I went out and started ascending. A thought above the Pastukhov Rocks I came up with a team of nine. The Japanese were hardly moving on. Things were in a bad way with them. Having attended them up for about an hour, I invited them in broken English to come down to the Shelter for fear of consequences. Having conferred between themselves, they agreed to it and, dejected, began to plod along on their way down. As for me, I kept ascending and, having passed so-called the ‘Slant Traverse’, reached the Col where I met Junka Tabei and her three female companions, very graceful girls. They had already reached the Eastern summit and were slowly descending.

It is considered by many that Alpinism isn’t meant for women because of the overstrains this sport involves. Methinks, however, the ascent rather demands will to win and survive than merely physical strength. As to the former the women who have devoted themselves to mountaineering are lavishly endowed with it.

I saw the girls to have exerted themselves hard. It had cost them much effort to pay homage to Elbrus. They barely could stand on their feet. I took out of my backpack a vacuum flask filled with hot tea and treated them to it. They revived a little. I seized their backpacks, walking alongside of them. Every now and then the Japanese girls were ready to drop with fatigue but nevertheless they were forging ahead. Here it is worth mentioning that even Norgei Tenzing in person, the first man to reach the top of Everest, had not succeeded in ascending Elbrus hard as he had wanted to do so. He had dismissed the matter with a joke: Elbrus, he had said, hadn’t deigned to concede his request for an ascent.

Over the wireless I asked the rescuers who were on duty at the Shelters to meet us. The Japanese had taken with them ski-tours and planned, using that convenient transport, to go down from the summit. But they could hardly carry them as far as the Pastukhov Rocks. Now we had to take away their equipment and escort the exhausted women down to the Shelter. Accompanying the Japanese, I helped now one young lady, now another to get up from the snow. Junka Tabei felt better than the rest but even she could hardly walk. I was cheering up the girls, offering them warm tea. Just before one comes to the Shelter, I left them behind and apace went down alone in order to have time to boil water and make tea by their arrival.

In the issue they dragged themselves home and saw on the table the same simple fare. At that very instant a jolly crowd of Americans accompanied by Valentin Ivanov, a noted mountain-climber, burst into the saloon. They filled not so great a room with laugh and merry-making. Ivanov’s assistants quickly laid the table, spreading out all kinds of delicatessen: fresh vegetables, fruits, smoked sausage, pressed caviar and other nice food rich in calories. Valentin, introducing me to the Americans, told them about our rescue service and asked the guests to sit down to table. I was ill at ease, founding myself in an awkward situation. What a striking difference of the menus, the Japanese one being in so a drastic contrast with that of the Americans. Having sat for a while in common decency, I returned to our frugal diet. Meantime Junka, addressing me in broken English mixed with Japanese words and eager to say something important, little by little was getting sorer and sorer at me. I asked the interpreter to explain what a grudge she had against me.

“You treat the white better than us belonged to the yellow race. Why on earth have the Americans such a lavish ratio, and we have none of what they have? Where are our guides? Where are our altitude porters? Why haven’t you secured our ascent? We have paid for all, have we not?”

“Explain to her, please”, retorted I through the interpreter, “she mistook for somebody else. I am a rescuer, and my functions are here to help people without respect of person and regardless of class and race affiliation. I don’t care a brass farthing for their skin colour though it were dapple-gray. Therewithal, we warn them of eventual dangers on the Mountain, and it is not our fault if they disregard our warnings thereby complicating their climbing or even frustrating their plan. As for the provision, the guides and the like these problems do not concern me at all”

“But you have helped us on our way down but it will not do. You are here out on Elbrus slopes a representative of your native country and you are obliged to secure the ascent of Elbrus for the whole of us”

“I can’t answer for Soviet power in general, still less for the people who have invited you here, dear Junka, to climb Elbrus and who to boot have got money in advance for their job to come. Concerning the assistance I have rendered to you, I have done it not in the line of duty but I considered it an honor to help the first woman who had succeeded in climbing up to the top of Everest”

Junka kind of calmed down and invited me to call on her in her room. There she showed me the contract. The interpreter translated it into Russian word for word. It was my turn to be embarrassed. The contract with ‘Sovintersport’ (Soviet organization that was entitled to transactions in the line of international tourism, exchange of hiking and mountaineering teams, and the like. – translator’s note) had a provision where it was stipulated for appointing a guide each of the thirteen Japanese climbers, and another one charged with inspecting the glacier for the purpose of detecting possible crevasses on the way up and down, the guide going ahead of all. Moreover, five altitude porters should carry the climbers’ things. To be sure, it was stipulated for getting meals rich in calories, and the receiving party guaranteed that all the thirteen mountaineers would climb up to the summit of Elbrus. Each member of the Japanese team had paid in Moscow one thousand dollars for a day-long sojourn in Baksan valley, including all the above-said services. To sum up, seventy eight thousand dollars had been paid down for those would-be facilities and conveniences… I tried to have it out with her that I had nothing to do with the contract, I was clear an outsider here, I had no interest in it… but she seemed to mistrust me. By the by, Leonid Andreev had not been told about the terms of the contract either. ‘Sovintersport’ big operators knew what’s what.

When the snow-storm had subsided the Japanese said good-by to us and went down.

Three months later I received a very cordial letter with apologies and best wishes from Japan. It was from Junka Tabei. She had enclosed into the envelope some stills and had written that she had gained an understanding of who is who.

Some more time had elapsed, and the friends made me feel the mountaineering sympathy – what is it like?

After Chernobyl disaster my daughter had been suffering from thyroid gland’s swelling. The doctors advised her to apply sea-kale. I phoned my friends from Baku and asked of them for it. A friend of mine Rassim Jafarov, an instructor of mountaineering and my rope partner, sent it in plenty at once. Therewith, I got to know that a medical treatment had been developed in Japan as applied to thyroid gland and using a medicine which proved to be very effective. Without a glimmer of hope for any positive issue I wrote a letter to Junka Tabei. She straight off sent the medicine. So, thanks to the common efforts of my friends, my daughter recovered from her illness.

vklestov, Thank you for your very interesting story !

Были ли на Коммунизме - не помню.

В книге В Эпова "От Ачик-Таша до Эвереста" есть снимок с подписью--на пике Ленина.

На самом деле снимок сделан на Коммунизма-японки и три (из четырех) вышеупомянутых гида-тренера